The life and death of Yukio Mishima: A tale of astonishing elegance and emotional brutality www.independent.co.uk

On YouTube you can find a couple of videos of the Japanese author Yukio Mishima being interviewed in English, conducted in the late 1960s. In one, the grainy black-and-white footage features Mishima talking about hara-kiri, the ancient form of ritual suicide practised by Japan’s samurai class. He spoke first about what he saw as two “contradictory characteristics” of the Japanese; elegance and brutality. He said: “The two characteristics are very tightly combined, sometimes, and the brutality I think comes from our emotions. The elegance comes from our nervous side, and sometimes we are too sensitive about defining elegance or sense of beauty.”

As an example he said that in the samurai tradition – Mishima was descended from Japan’s warrior class – “duty was always connected with death” and if a samurai committed the ritual suicide he was “requested to make up his face with powder or lipstick in order to keep his face beautiful after suffering death”.

Elegance and brutality. But, noted Mishima, hara-kiri was very different from the western notion of suicide, which he said was born of defeat. He added: “Hara-kiri sometimes makes you win.”

We’ll tell you what’s true. You can form your own view. From 15p €0.18 $0.18 USD 0.27 a day, more exclusives, analysis and extras.

In November 1970, probably just a year after that interview, Yukio Mishima knelt down on the floor in the offices of the Japan Self-Defence Forces at Ichigaya Camp near Tokyo. The commandant was tied to a chair, the office door barricaded. Mishima, along with four members of his own private militia, the Tatenokai, or Shield Society, had inveigled their way into the office. Their intention was to instigate a military coup. It failed. Mishima, who was a couple of months shy of turning 46, took the warrior’s way out.

Kneeling on the floor, he disembowelled himself with a dagger. He had committed a form of hara-kiri called seppuku, which was traditionally practised by samurai who wanted to die with honour rather than fall into the hands of their enemies. Looking at Mishima’s life and death, it’s easy to forget that he was, in fact, primarily a novelist. He trained as a samurai himself, he was a bodybuilder, he acted in movies and modelled in photoshoots.

In fact, he left behind an astonishing literary legacy. Thirty-four novels, 25 collections of short stories, 50 plays, and 35 books of essays. His novel-writing career began in 1948 with Thieves, and was followed up by the book that propelled him into the literary limelight, Confessions of a Mask. A good number have been, at one time or another, translated into English.

Perhaps Mishima’s best-known works in the west are The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea – an almost Lord of the Flies-esque story of a group of teenage boys who reject the adult world until one of their mothers falls in love with a naval officer. At first, they idolise him, and then reject him, in brutal and violent fashion – and The Sound of Waves, a love story set in a remote fishing village. His final works, the Sea of Fertility tetralogy, comprising the volumes Spring Snow, Runaway Horses, The Temple of Dawn and his last novel, The Decay of the Angel, are a Proustian epic detailing Japan’s history from 1912 and the beginnings of the intrusion of the outside world.

Had he not written a single word, Yukio Mishima’s life would have been interesting enough. But the astounding body of work he left behind is truly the work of a genius, though a complicated, troubled and not always comfortable one

But now there is a “new” Mishima, or at least one that is being published in English for the first time. Originally serialised in the Japanese edition of Playboy magazine, Life For Sale was first published in Japan in 1968, two years before his death. Penguin Classics will release the first translation of it, by Stephen Dodd, on 1 August.

Mishima veered between literary novels and mass-market, almost pulpish fiction, and Life For Sale falls firmly into the latter category. It has recently found a new audience in its native Japan, and sold hundreds of thousands of copies. It’s an at times absurdist tour de force, about a young man called Hanio Yamada who tries – and fails – to commit suicide, and with nothing to live for and feeling rejected even by death, puts an advert in the local paper.

“Life For Sale,” reads the ad. “Use me as you wish. I am a 27-year-old male. Discretion guaranteed. Will cause no bother at all.”

But Yamada does cause quite a bit of bother, as a procession of grotesque characters take him up on his offer, from spies to junkie heiresses to mobsters to even vampires. It’s funny and horrific and curious and thoroughly entertaining and should win Mishima a new generation of fans, especially those who have not embraced his more literary fare.

But just what are they getting themselves into? Mishima was a pen-name; he was born Kimitake Hiraoke on 14 January 1925 in Tokyo to a father who was a government official and a mother who was a scion of an aristocratic Japanese family. His grandmother, Natsuko, took control of the boy’s upbringing for many years, going so far as to separate him from his parents and bringing him up in a solitary existence. He was banned from playing sports or engaging in rough and tumble with other boys, and when he was allowed friendships it was only with his female cousins.

When Mishima was returned to his family, at the age of 12, his father immediately tried to toughen his son up. There is one story that he held the young Mishima up dangerously close to a train that was speeding past. Mishima, even at that age, was already displaying literary tendencies, which his father considered “effeminate” and responded by ripping up anything the boy wrote.

Perhaps this unorthodox upbringing is what informed Mishima’s thoughts on the dichotomy of brutality and elegance he vocalised in that interview shortly before his death. That said, his grandmother Natsuko was given to often violent outbursts herself.

Despite his father’s protestations and best efforts, Mishima continued to pursue his literary ambitions, voraciously reading both Japanese and western literature through his teens, and his first short story, Forest In Full Bloom, was picked up by a literary magazine and published as a book in 1944, when he was still at school, aged 19. It was then that the pen-name Yukio Mishima was adopted, said to be an invention by his teachers who wanted to keep him safe from the bullying of his schoolmates at the elite, rugby-playing Tokyo school he attended, whose students were evidently of the same mind as Mishima’s father about the masculinity of literary pursuits.

By the age of 24, Mishima had become a certified literary sensation. His first novel, Thieves, is about a pair of youths from the upper echelons of Japanese society who flirt with the idea of suicide. His second, Confessions of a Mask, concerns a gay man who hides behind a literal mask to disguise his true nature in Japanese society. His works were translated and he gained a sizeable following in the west, and he was nominated three times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, though never won it.

By 1960 he was acting in Japanese movies, most notably that year’s Afraid To Die, about Japan’s organised crime syndicates, the yakuza. He even sang the theme song to the movie, and had roles in several other films, including one he directed himself in 1966, Yukoku. Added to that, he was a model for the Japanese photographer Tamotsu Yato, who was famed for his homoerotic, monochrome imagery.

In those post-war years in Japan, and heading through to the Sixties, a time of change across the world, it would seem reasonable that Mishima would be something of a counter-cultural icon. His novels often dealt with difficult or taboo subjects. Given his upbringing, switching between a militaristic father and his odd maternal grandmother, he might have been expected to eschew both worlds and forge a new path.

After all, that post-war period was the time of the Beat Generation, the likes of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassady, turning their backs on the shiny American dream of labour-saving kitchen appliances and nuclear families and searching for their own place in the world. He was a contemporary of Kerouac, born just three years after him.

And, there are indeed some parallels. The Beats were all about freedom and experimentation, with drugs, lifestyles, sexuality. Mishima, while researching his novel Forbidden Colours, started to frequent gay bars, something which is said to have troubled his wife, Yoko Sugiyama, whom he married in 1958. But in 1967, Mishima did something perhaps unexpected for someone with literary stardom at their feet and a radical oeuvre of books. He joined the military.

This ‘Shield Society’ had the most nationalistic of missions: to serve and protect the emperor of Japan

Mishima was already 42 when he enlisted in the Ground Self-Defence Force, essentially Japan’s land army. He underwent the rigorous training, but he had a longer game in mind than merely sudden patriotic urges. A year after joining up he left, and decided to form his own army. The Tatenokai was a private militia mainly recruited from student bodies at universities. It had uniforms and discipline and looked for all the world like the real deal. This “Shield Society” had the most nationalistic of missions: to serve and protect the emperor of Japan.

That, however, did not necessarily mean Hirohito. In 1946, at the behest of General Douglas MacArthur, who was in charge of the Allied post-war occupation of Japan, Hirohito issued a statement called the Humanity Declaration that turned its back on the long tradition of the Japanese emperor and stated quite firmly that he no longer believed himself to be a living god.

Mishima was incensed, and wrote a long piece denouncing Hirohito’s decision, saying that those who had died for Japan in the war had done so for their living god of an emperor. He continued to write novels and plays, producing what many consider his masterpiece, the Sea of Fertility sequence, in the final years of his life. But he had his eyes on a prize other than merely literary fame.

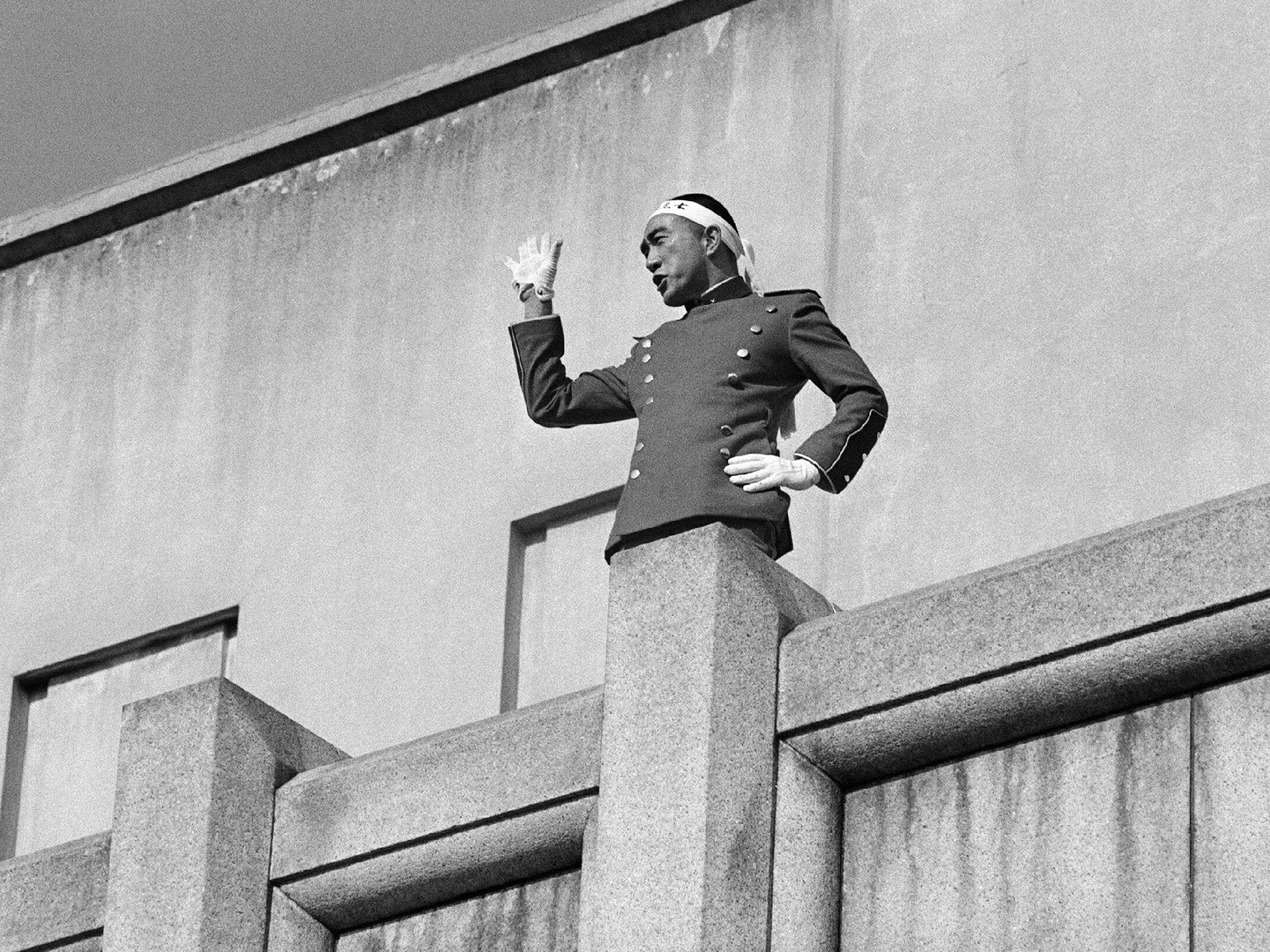

When Mishima and the four members of his Shield Force marched into the commandant’s office in November 1970, he believed he was leading a military coup. After tying up the commandant and having his soldiers barricade the room, he stepped out on to a balcony to address the regular soldiers gathered in a courtyard below. He read them his declaration, that he was now in charge of the military and that they were going to lead a coup to restore the old ideal of the “living god” emperor to Japan.

The soldiers laughed at him. Their mockery ringing in his ears, Mishima went back into the room, knelt on the floor, and in the manner of the code of bushido, the way of life that governed the samurai from which he was descended and which he believed to be, he stuck a knife into his abdomen and allowed his intestines to spill out on the rug.

It all might have been straight out of one of the most absurdist Mishima novels, especially what happened in the aftermath. Seppuku demands that the dead warrior is beheaded; one of the militia tried three times before another took over and completed the task, right there in the office. As was tradition, the beheader then committed seppuku himself.

Suicide is a constant theme in much of Mishima’s work, including in the latest novel to get an English translation, Life For Sale. The book opens with Hanio Yamada being roused from his failed attempt to take his own life. Mishima wrote: “Suicide was not something he had put much thought into. He considered it likely that his sudden urge to die arose that evening while he was reading the newspaper – the edition for 29 November – at the bar where he normally ate dinner. It contained the run-of-the-mill sort of stuff, of no special significance. All the articles left him totally cold.”

But there is some suggestion that Mishima did indeed plan his own death, and that the whole coup was merely a vehicle to get him to the point where, knowing it would obviously fail, he could commit seppuku. In his book Mishima: A Biography, John Nathan – who also translated some of Mishima’s fiction – said that before the coup attempt the writer had put all his affairs in order and made provision for the legal representation of the Shield Society soldiers he had involved in the enterprise.

Had he not written a single word, Yukio Mishima’s life would have been interesting enough. But the astounding body of work he left behind is truly the work of a genius, though a complicated, troubled and not always comfortable one. Life For Sale might not necessarily be his finest work, but the sheer, audacious insanity of this novel is a fine place with which to start to discover this most complex of 20th-century literary figures.